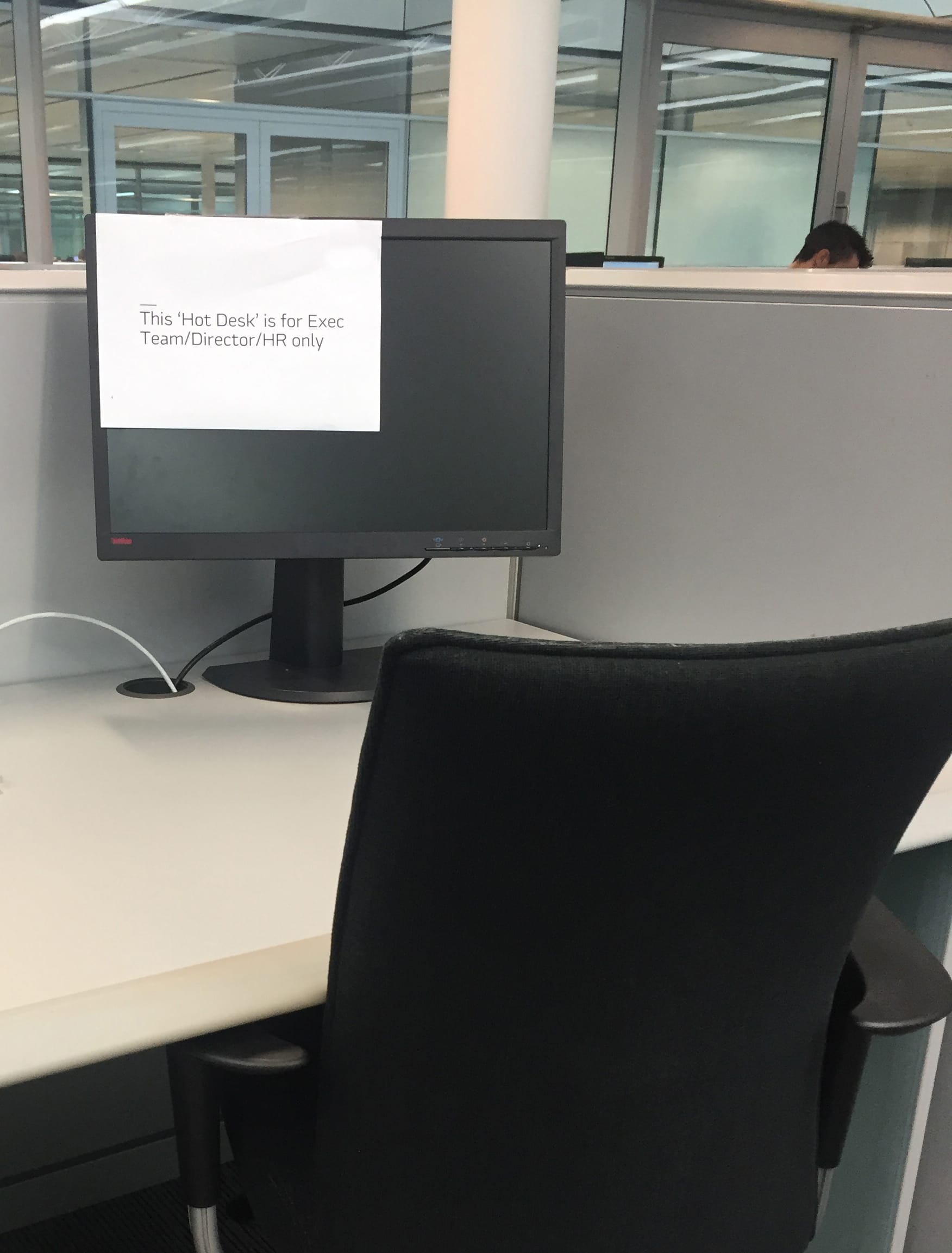

On the so-called ‘hot desk’, someone had taped a sign: “For Exec Team / Director / HR only.” A single sheet of A4 told the loudest story in the room. It’s not the sign that’s loud; it’s what it says without saying.

A desk meant to be shared suddenly becomes a symbol of exclusion. One small cue reveals what the organisation truly values.

And that’s where the idea of Cues & Clues began for me.

Because spaces are always speaking. The question is: are we listening?

That moment - the sign, the desk, the contradiction - reminded me that space isn’t neutral. Every environment broadcasts a thousand micro-messages about what’s valued, what’s allowed, and who belongs.

I call these signals Cues and Clues.

Cues are intentional: the things we design to send a message or evoke a response. They might be spatial (lighting, layout), operational (rituals, signage), or social (tone, behaviour). A well-placed cue can invite, guide, reassure or inspire. Think of it as a kind of silent choreography shaping how people move and feel.

Clues, on the other hand, are unintentional: the traces of how people actually behave within those designed conditions. They’re the scuffs on the floor where everyone cuts the corner; the meeting-room chair that’s permanently claimed by an unspoken hierarchy; the extra monitor someone’s snuck in because the setup doesn’t quite work.

Cues reveal intention.

Clues reveal truth.

Together, they form what I think of as the silent script of space: the interface between design and lived experience. When the cues and clues align, we feel flow, ease, belonging; what I call spatial resonance. When they clash, we feel friction, frustration, or subtle exclusion.

And the magic (or mischief) is: most of this happens beneath conscious awareness.

Why it Matters

When we pay attention to the cues and clues in our environments, we begin to see the real dialogue between intention and experience.

Because even the most beautifully designed workplace can fall flat if the signals contradict what people actually feel. A sign that says “Everyone’s welcome” means little if the clues, (the closed doors, the corner offices, the cautious silences), tell another story.

Cues and clues are the interface between what we say we value and what we really do. When they align, the space hums. People relax into it. They behave naturally, confidently, creatively.

When they’re out of sync, the dissonance is palpable, though rarely spoken. People adapt, workaround, withdraw, or even revolt. They form habits that whisper, this isn’t really for me.

In that sense, noticing cues and clues isn’t just a design exercise; it’s an act of empathy. It’s a way of tuning into the undercurrent of an organisation, the unsaid truths that live in the walls, the routes people carve, the gestures they repeat.

And the moment we start noticing them, we start to see an opportunity to realign intention and experience, to bring the environment back into resonance.

Stories Spaces Tell

The Agile Classroom That Wasn’t

Back in 2014, the first module I taught as an adjunct professor at IE University was called The Agile Work Space. The irony wasn’t lost on me.

I arrived halfway through the semester to find twelve postgraduate design students scattered across a room built for fifty. The space was shallow and wide, with four endless rows of tables stretching across it, like layered barricades between me and them. It felt less like a classroom and more like a control room from a post-apocalyptic film; barrier after barrier to cross before we could even connect. We were not odd to a great start; by the time I noticed the third student nodding off, I realised I had to do something.

So I ditched the plan and got everyone to deconstruct the room itself: to inspect every element and ask what it was really for. One group discovered that the heavy-looking tables were actually foldable and on casters. This was a revelation to the whole class; they’d been in that space for six weeks and had no idea they could move them.

When I asked why, they said, “We just assumed we weren’t allowed”.

We folded the tables away, created clusters for conversation, and the energy in the room transformed instantly. At the end of our session, I asked the students how they wanted to leave the space. Rather than put the tables back in rows, they decided to stack everything away tidily and leave a note for the next professor saying:

“Dear Professor, please arrange the room in the way that best supports your session.”

That moment revealed something profound about spatial permission.

Even in a room designed for agility - taught by people studying agility - the students had assumed they couldn’t move a thing. It was a reminder that permission rarely happens by accident. The cues that grant it are often invisible or unintentional.

We can design spaces full of flexible furniture, but if the culture, layout or social signals say “don’t touch,” people won’t. Designers might create the physical elements, but it’s just as important to design the behavioural layer: the way people are invited to use, adapt and inhabit the space.

True flexibility isn’t about furniture on wheels. It’s about whether people feel allowed to move it.

The Lost Visitors

Several years earlier, I was consulting for a global company whose facilities team prided themselves on excellence. They regularly surveyed staff and visitors on service quality. The results were strong across most categories, except one: Visitors felt unwelcome.

When I asked why, the team shrugged. “It’s always low,” they said. “There’s nothing we can really do about it.”

That comment stuck with me.

Later, during some ethnographic observation work, I noticed something small but revealing. The campus had two identical buildings: the right-hand one housed reception, the left-hand one was off-limits and guarded for security. Yet the company’s giant logo sat proudly on the left-hand façade - not the right.

So visitors, dropped off by taxis, instinctively headed toward the big name. Only to be met by a baffled, sometimes brusque security guard asking what they were doing there.

No wonder visitors felt unwelcome: the space was literally sending them to the wrong door.

The DreamWorks Path

At DreamWorks’ campus, the designers created a gently sloping zigzag path between two main buildings - almost like a ramp, lined with low hedges on either side. It was intentionally slow: a designed pause between meetings, encouraging people to step outside, breathe, and reset before heading back indoors.

Over time, though, a new path began to appear: a worn track running straight down the side of the ramp. It was the faster option, carved by people taking the most direct route.

What I loved was that both paths remained. The design team didn’t block or reseed the shortcut; they accepted it as part of the landscape. The zigzag invited reflection, the side path offered efficiency: two parallel modes for different moments.

It was a small but generous gesture of design maturity: an acknowledgment that we can invite people to slow down, but we also need to respect that sometimes, they can’t, or shouldn’t.

How to Notice and Design for Cues and Clues

Once you start tuning in, you can’t unsee it.

Every environment is communicating - through its layout, materials, rhythms, and rituals - about what’s encouraged, what’s tolerated, and the unspoken ground rules people live by. Some spaces reinforce those rules; others rewrite them.

The key is to move from seeing spaces as fixed backdrops to recognising them as living systems that both shape and respond to behaviour.

Here are a few ways to start noticing:

- Follow the flow. Watch where people actually go, not where the floor plan says they should. Desire lines, bottlenecks, abandoned corners - these are all clues about what works and what doesn’t.

- Read the room, literally. Look at artefacts, signage, and improvised fixes. What do they say about permission, hierarchy, or care? A hand-written note, a personal mug, a locked cabinet. Or worse, a passive-aggressive notice from “Management.” Each reveals whether a culture treats people as trusted peers or unruly children.

- Observe the workarounds. When people drag furniture, block light, or bring in their own tools, they’re signalling unmet needs. These clues are often more revealing than any survey or data-set.

- Listen for friction. Notice where people hesitate, apologise, or ask for permission. These are the moments that point to missing or muddled cues.

- Design the interaction, not just the object. The most effective cues aren’t always physical; they’re cultural. They live in tone of voice, humour, rituals, and moments of invitation: ways a space encourages people to engage, not just behave.

The best workplaces use their environment to communicate with wit and humanity, reminding people that they’re part of the story, not subjects of the rules.

Every space sends a message. Our job is to make sure it’s the right one.

When we read the clues and design the cues with care, we move beyond aesthetics to influence how people think, feel and connect. That’s the real work of spatial resonance.