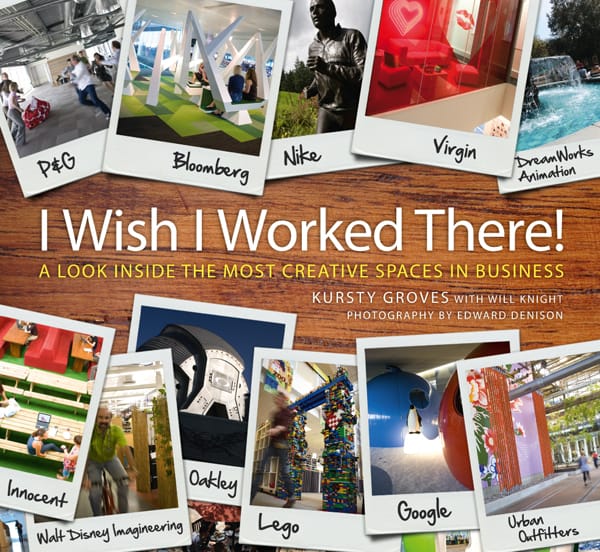

Fifteen years ago, I Wish I Worked There! hit the shelves.

But the story started long before that. In 2007, I set out on what I thought would be a three-month sabbatical to write a book. It turned into a cross-continental adventure, a creative deep-dive, and the backdrop to one of the biggest personal transitions of my life.

Armed with a camera, a notebook, and (eventually) a bump, I visited 20 of the world’s most creative workplaces. Not just to admire the architecture, but to understand something deeper: how space shapes culture, connection, and innovation.

This is the real story behind the book: Why we did it. How we did it. And what happened next.

Why We Did It

At the time, I was working at an innovation company called ?WhatIf!. We helped organisations solve big problems and build their creative muscle through mindset, behaviours, culture, and tools.

I was surrounded by creativity every day - teaching innovation skills, coaching teams, facilitating workshops. Helping others uncover insight, generate ideas, shift behaviours and spark change inside their organisations.

But I missed design. I missed getting my hands dirty. Making something of my own. I loved guiding others, but I wanted to create my own thing from scratch. Something I could shape, wrestle with, and eventually hold in my hands and say: I made this.

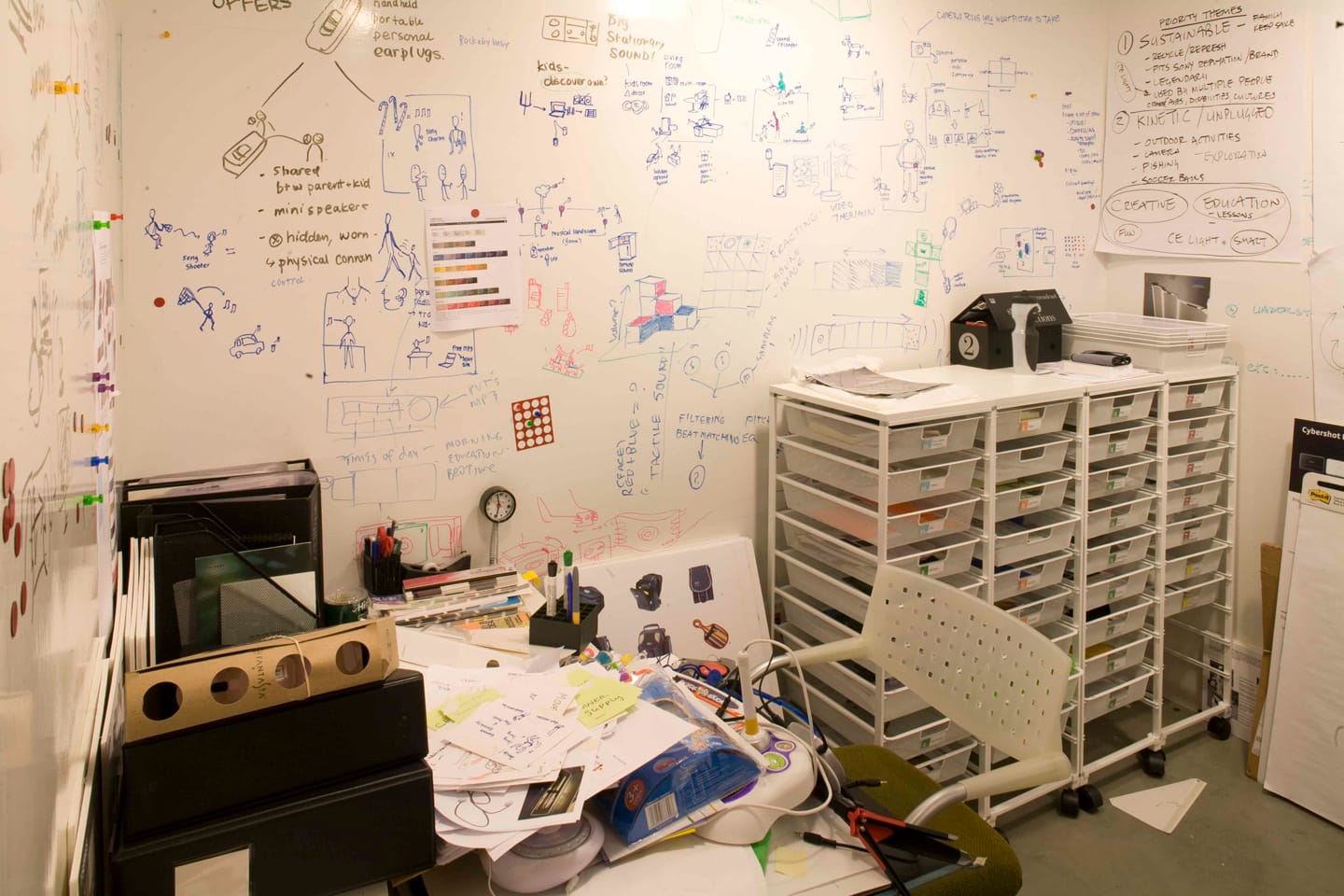

At ?WhatIf!, we talked a lot about barriers to creativity - and how, with the right mindset, those barriers could become enablers. Space was often mentioned, but only lightly. It always felt like we were just scratching the surface. And I kept thinking: We’re missing something important here.

I couldn’t shake the feeling that environment mattered. Not just as a backdrop, but as something more active. Something that could unlock energy, shift behaviour, maybe even support culture. I didn’t know exactly how it worked, but I had a hunch that space could be more than a container for ideas.

I started noticing that some organisations were already acting on that hunch. They were paying attention to their physical environments - and not in surface-level, stylistic ways. They were doing things differently. Valuing space. Investing in it. Using it deliberately.

I wanted to know why.

Stories were emerging from places like Google. It was 2007: the year the iPhone launched. The idea of work was shifting fast. Rumblings of change were in the air, but those now-iconic creative campuses didn’t exist yet.

Work was changing rapidly. Digital tools like the iPhone were just launching, promising new ways to connect and communicate. Stories were emerging from brave companies like Google who were rethinking the spaces where people spent their days. These early experiments were the seeds of something big, even if the iconic campuses we now admire were still years away.

Separately, I began quizzing Ed Denison - a university friend of Will’s - who had written several books on architecture and design. Every time we saw him at weddings or parties, I’d pepper him with questions:

How do you do it? How do you get published? How do you know when an idea is really a book?

I was fascinated. Not just by the process, but by the possibility. I think part of me genuinely believed that old saying: everyone has a book inside them. (Though Twain probably added that’s exactly where most of them should stay.)

One day, after yet another of my wedding-reception interrogations, Ed said, “Write a pitch. I’ll introduce you to my editor.”

So I did. And he did.

That introduction set everything in motion. But once the pitch was in progress, I almost gave up. It was overwhelming, and I wasn’t sure I had a clear enough story to tell. Then a nugget of clarity struck me: this wasn’t just about spaces or buildings - it was about the people inside them, their behaviours, their culture. The story I wanted to tell had to be about their experience, not just architecture.

I started digging - into books, articles, case studies. Most of what I found were glossy portfolio pieces. Beautiful, yes. But sterile. Designed to showcase the work of designers, not the lived experience of the people inside. The spaces were pristine, stylised, and strangely empty. If people appeared at all, they were props: perfectly posed, incidental at best.

Then I found Marilyn Zelinsky’s New Workplaces for New Workstyles. And for a moment, I panicked. Had I missed the boat? Was this the book I was trying to write?

But the more I read, the clearer the gap became. She offered a broader lens than most - touching on things like amenities, visual interest, and some of the peripheral elements of creative work. But she didn’t go deeper into workplace culture. She wasn’t drawing from lived experience inside innovation teams. And she wasn’t speaking to the kind of messy, complex, constraint-heavy creativity I was seeing in big organisations.

What I realised was: she didn’t have my lens. She wasn’t focussed on how space could unlock (or stifle) behaviour, or how it could support the specific rhythms of creative work in large companies.

That was the thread I wanted to follow.

At first, I thought I’d focus on creative agencies. But that felt too obvious. Too easy. I wanted to go where it was tougher. Where space had to work, not just look good. I wanted to see how global companies - the ones juggling legacy systems, red tape, and real constraints - were using their environments as tools for creativity, connection, and change.

That’s where the real stories were.

How We Did It

After Ed introduced me to Helen Castle, a commissioning editor at Wiley, I pitched the idea. Helen saw potential and encouraged me to develop it further.

Publishing was in flux. Digital was shaking things up, and as a first-time author I was considered high risk. Helen held the line. The book didn’t fit neatly under “business” or “design,” but she believed in the vision and gave us a chance. Part of the deal was that I had to commit to buying back 250 copies of the book myself. Not exactly the cushy advance I’d imagined. But the hope was that the companies featured would want to bulk order. Thankfully, they did.

We didn’t have much spare cash. We’d just sold our London flat, right before the financial crash hit, and were living in New York. That sale paid for our wedding, the travel it took to make this book, and gave us a buffer during a time that would test us more than we expected.

My employer granted me a three-month sabbatical. It wasn’t enough time to write the whole book; that would have been wildly optimistic. But it was enough to plan, schedule, and visit most of the companies.

Just after the sabbatical was confirmed, I discovered I was pregnant. So, with a growing bump, I set off on what turned into a whirlwind of research visits.

We built our list the old-fashioned way, through research, instinct, and introductions. I was after organisations known for innovation, but not just the obvious creative agencies. I wanted to see how large, complex businesses were using space creatively despite their scale and constraints.

Getting Google and Procter & Gamble on board made all the difference. Once they said yes, others followed.

In total, I visited over 50 companies. Twenty made the final cut. Some dropped out. One folded mid-process after I’d already written their chapter. Others didn’t quite live up to their promise once I got there.

The process was beautifully scrappy. I’d visit first, taking recce photos, doing interviews, sketching out the narrative. Then Ed, an architectural photographer, would return to shoot the final images. When he couldn’t make it, Will stepped in. A few of my original photos even made it into the book.

We experimented with long exposures to capture ghosted movement: people in motion, culture in motion - a way of showing the energy of a place, not just its physical contents.

The final sprint was intense. Two full chapters were due: words, images, captions, permissions - everything. I typed the last caption and then went into labour.

Jack arrived. I still had 18 chapters to write.

We were living in a tiny loft apartment in Williamsburg. Beautiful but cramped. The baby could smell me through the walls. No one was sleeping.

Eventually, we moved in with my mother-in-law in the UK. That’s where I wrote the rest of the book, one feed, one nap, one sentence at a time.

It took over two years, start to finish.

We began in 2007.

I Wish I Worked There! launched in March 2010.

What Happened Next

When the book launched, the response was more than I could have hoped for. It caught the attention of The Guardian, the Financial Times, Dezeen, Office Snapshots, and BBC Radio. FastCompany’s Polly LaBarre called it a “coffee-table business book” - a perfect blend of visuals and substance. Within three months, we had sold out the entire three-year print allocation.

Coca-Cola reached out, inviting me to speak to their global workplace team ahead of a major headquarters transformation. Soon after, Centrica called. Then Bacardi. That was the beginning of my solo consulting journey.

At first, I worried that architects or designers might see me as a threat. But that fear quickly dissolved. Instead, I found myself acting as a translator: helping organisations clearly express what they really needed from their workspaces. I helped designers find creative freedom within frameworks that truly supported the people who would live and work in those spaces.

That’s how my practice took shape: bridging vision and execution, turning abstract ideas into language, tools, and choices that could be designed with, not just around.

What has stayed with me most is the idea of designing from the inside out. Space is never neutral. It speaks. It sets the rhythm. It shapes relationships. It can either support or suppress how we behave, create, and connect.

Some stories from those early visits still echo in my mind. Philips Design, for example: modest, timeless, and meticulously cared for. A space that was ten years old then, but still utterly relevant. Or Google Zurich, with its igloos, fire poles, and lava lamps. Easy to mock, often misrepresented in copy & paste office fails, but actually deeply intentional. A culture of speed made visible.

I started out thinking that I was researching space. But really, I was learning how space holds us, and how it shapes who we become.

Today, my perspective has broadened. I consider not just physical space, but social spaces, digital environments, cognitive realms, and temporal rhythms. Human performance sits at the heart of my work, because creativity and productivity both need care. And that care lives in the details: in how we work, where we work, and the environments we choose to create.

Fifteen years later, the world of work looks very different. But some signals - the ones that truly matter - remain constant.

I’ll share more reflections on that journey soon.